|

-0 |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

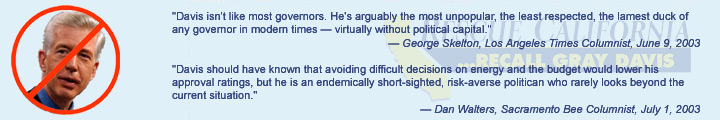

Recall booster finds fuel It was early January, and Kaloogian was now two years out of state politics. He was looking for something to do, and "recall was in the air," he said. Kaloogian jumped in with Sal Russo, Bill Simon's chief campaign strategist. A few days earlier, on Jan. 24, Russo had met with a group he described only as "some Democrats who will go unnamed for obvious reasons." Over lunch and iced tea at the Sutter Club, a popular political meeting spot near the state Capitol, the disgruntled Democrats urged Russo to help engineer a recall, Russo said. "They were aware that Davis' poll numbers were abysmal," said Russo. "They were uncomfortable with the idea that (Costa's group) was going to do this. They said they were not comfortable rallying around a taxpayer group, that it had to be broad-based." Recall backers have taken pains to strip the public campaign of a right-wing ideological bent. Just how involved some Democrats were in the early stages remains unclear. Russo was vague, saying they lent "some help in terms of opening doors." One Republican Capitol insider, however, said the interest was fleeting. Some Democrats and unions saw the two recall groups and feared a narrow, partisan campaign. "It was less than a week from 'This is interesting' to 'The hell with these idiots,'" he said. Clearly, many Assembly Democrats were fuming over Davis' budget priorities and his early threat to veto their proposal to triple car registration fees to help ease the need for deeper cuts. Labor unions -- traditional Davis allies -- were looking for leverage. They distributed polls that showed Davis' approval ratings plummeting, and negative impressions of him rising fast. The California Teachers Association, whose then-president Wayne Johnson had become a vocal Davis critic, conducted one poll in January. It showed Davis' favorable rating mired in the mid-20s. The point was not to entice a recall bid, said Johnson. "As the budget battle was coming up, we wanted to know how strong the governor would be in these internal battles in Sacramento. We put out information to Democratic legislators," said Johnson. "We weren't the only ones that were doing that." Kaloogian did not take long to jump at the chance to lead a recall campaign. "The first thing that went through my mind was all the objections: That we just had an election, and it was sour grapes," he said. "Then I came to understand the idea of a recall is not an impeachment. It's similar to a vote of no confidence. So the question is: Do you have confidence that Gray Davis can fix the problems now revealed?" Kaloogian and Russo formed the Recall Gray Davis committee. That made two groups coordinating a recall, and they wrangled over when to file papers, and who would submit them. Costa reached the Secretary of State's Office first. On Feb. 5, four days after Costa sat down in his kitchen, both groups announced their plans. A week later, in a formal response to the Secretary of State, Davis labeled the recall threat "partisan mischief" by "a handful of right-wing politicians." The numbers for Davis were bad and getting worse. A few local conservative talk radio hosts had begun to take up the recall mantle. But skepticism, particularly among the Republican Party faithful, still reigned. There was little reason to anticipate success.

In more than 100 attempts, just seven recall drives against statewide officials had made it on the ballot, and none succeeded. Pat Brown, Ronald Reagan, George Deukmejian, Jerry Brown and Pete Wilson were among 32 governors to weather failed attempts on their political

|

|

|